- Part I: Dr. Bin Song’s Explanation of “What is Philosophy”

Hallo! I am a Philosophy and Religion professor at Washington College. My Name is Bin Song. You can call me Dr. Song or Prof. Song. If we get along really well in time, I would not mind you calling me Bin or any other name you want. I was born in China in early 1980s, had studied philosophy, theology and religion in China, France and the U.S. for about 20 years before I came to Chestertown of Maryland in 2018. During this long period of academic training, I also did non-academic jobs such as being a journalist, a copy-writer, a part-time chaplain in a university church, and making smoothies in a shop of Jamba Juice at Boston. With all these life-experiences restored in my body and soul, let me explain the question “what is philosophy” to absolutely beginning learners in this episode.

I entered my college in late 1990s, and students in China at that time could not freely choose their majors, particularly when they happened to come from a place where so many applicants competed for the limited educational resource. It turned out that I was forced to learn philosophy. Yes, you didn’t hear it wrong. I was forced to learn philosophy, and the reason I got from the university which made the forceful decision was that students of higher examination scores need to be equally distributed in varying departments. So, I indeed got a relatively high score, and thus, in order to support the flourishing of philosophy, I was forced to take it as a major.

You must feel this is a terrible story for a freshman going to college for the first time in his life. Yes, that was terrible. My original plan was to become a poet and novelist, writing great literary books and interacting with readers as my career. By the way, this is actually one reason why I would like to work at Washington College. It has its Sophie Kerr literary prize, the amount of which is the highest in the country, and Washington College is therefore literally a writing college. Anyway, so I had to give up my original plan, was forced to learn philosophy, and lived through an extremely terrible life in my early college years.

I think the most unpleasant part of that experience for me is that as a young man, with an immature mind, I tended to perceive everything surrounding me, everything in the world, as gray and gloomy just because of the one setback I had experienced in my life. For instances, I thought my parents were not kind, the government was not just, and none of my friends fully understood me, and so on. You know what I am talking about, right, since you are also in about the same age. I didn’t want to go to courses, I didn’t want to participate any student activities, and I just hid myself in the library to read everything that I can grab about poems, novels, and literature all days along.

One conclusion I can reach about that period of my life is that: when what you want cannot line up with what the world offers, life will become a shred of plastic bag twirling and twisting in the wind: it is ugly, random, meaningless and hopeless.

So, there must be an outlet. Oddly enough, as you may have already guessed, the outlet for me is philosophy.

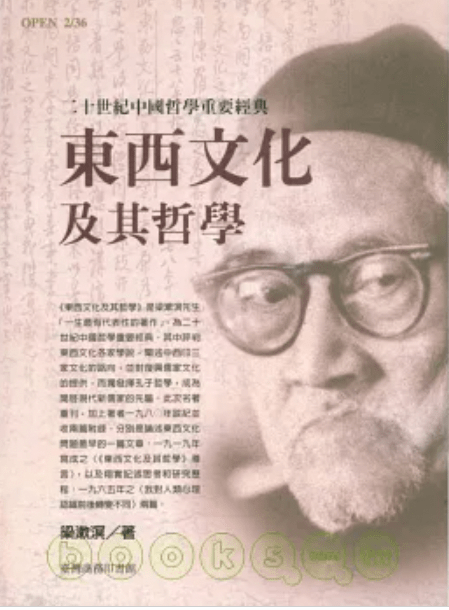

I clearly remember the changing event happened in the winter of 1999, which was also at the end of last century. After all courses were finished in the fall semester, I still did not want to go back home. For reasons I cannot explain even now, I went to the library and randomly picked up one book, since its title impressed me. The title of the book is “Cultures and Philosophies in the East and West” (東西文化及其哲學), which was written by Liang Shuming (1893-1988) in 1921. Then, I started to read it, mostly in a big auditorium classroom when very few students stayed there. Remember, that happened in a winter, cold, chilly, and my mood was no less gloomy because of reasons explained above.

I have to say a miracle happened to me. Without having a copy of the book in my hand now, I still clearly remember the major views of the book. So this is what the author told me at that time. He says,

The driving force of human life is called “will of life,” a will to live, a will to flourish, and a will to seek meaning and power for one’s given, yet limited and ambiguous human life. The best manifestation of this will of life is one’s desires. Desires of all sorts of objects: food, security, sex, fame, wealth, power, human relationship, meaning, etc. And there are three major different kinds of ways in the cultures of the world to deal with the relationship between one’s desire and its objects.

The first path is the western path. It tells that if you desire something but you cannot get it, then, the right way for you to deal with the situation is to step forward, advance yourself, and thus, try the best means to overcome any obstacle down the road so as to eventually get what you want, and satisfy your desire. But once your desire is fulfilled, this path will still urge you to seek more, grab more, and thus, be involved in a perpetual process of ego-expansion, self-aggrandization, and world-conquering.

The second path is the Chinese path, or using Liang Shuming’s term, the Confucian path. The path denies neither the legitimacy of human desire, nor the natural right of beings that are desired by human beings. For instance, if you ever ponder the issue of whether to be a vegetarian, a Confucian path would say: animals have their right of living, but humans also have their natural need to consume meat. Therefore, the right path to live through this apparent dilemma is that let’s keep both, but modify both so as to harmonize the needs of both in order to achieve a certain kind of co-thriving. In a more concrete term, this path will tell you, the human need to consume meat is natural, but it cannot go over its due measure. So let’s improve the meat industry to raise animals while treating them better, and also make sure not bring any other negative consequences to the environment such as global warming. So the Confucian path thinks human needs, desires, and emotions are natural. None of them are intrinsically bad, and all we need to do is to have them achieve the appropriate measure for the sake of harmony and co-thriving of all beings in the world.

The third path is the Indian way, the way best represented by a Buddhist ethic. According to Liang Shuming, when humans desire an object, the Buddhist ethic will deny the necessity of the desire all together. This is because firstly, unfulfilled desires always cause suffering, and secondly, even if we fulfill some of our desires, another desire will follow; once fulfilled, another desire will follow; and in the process, we would be never genuinely happy because there are always unfulfilled desires in our life. Therefore, the Buddhist solution is that, let us simply not desire. That means to eliminate human desires by all sorts of methods. For instance, Buddhist philosophy will teach you how illusory your understanding of the world is, and the Buddhist tradition also includes many skills of meditation so as to have you focus upon the right understanding of the world, and eliminate those desires that caused your suffering.

In a nutshell, according to Liang Shuming, when we desire any object to manifest the will of human life, the western path wants to overcome the obstacles of human desires so as to chase objects while fulfilling those desires. The Confucian path wants to harmonize the desires and the objects so as to achieve a certain degree of co-thriving. Meanwhile, the Buddhist path eliminates desires all together to avoid suffering. So, comparatively speaking, the western path is a path forward, the Buddhist path is a path backward, while the Confucian one lies in the middle. In the time of Liang Shuming’s life, the early 20th century, China was experiencing a profoundly dire situation of national disintegration triggered by the challenge of western colonial and imperial powers. According to Liang Shuming, the unique situation of China in the 20th century made it necessary for Chinese people to learn more about the western path, solidify its traditional Confucian path, and abandon the Buddhist path all-together.

I have to confess you that this book has made a huge impact upon my gloomy and grouchy life in my late adolescence. Firstly, it tells me what the world is. Secondly, it lays out varying paths of life so that I can envision a purpose of my own life. Thirdly, it also inspires me about what I can do for the world.

Apart from the philosophical knowledge I get about the world from the book, I feel a great therapeutic effect of its philosophy upon me. For the first time in my life, I realized that I have some natural tendencies in my body , the value of which I cannot deny. Instead, through cultivating these tendencies, I can get along with the world well, and make a contribution to its thriving while flourishing my own life. So, as you may have known, I was tending to choose the second path of human life explained by Liang Shuming, that is the Confucian, middle path, since it tells me I can get along with both myself and the world in a time when this message was so badly needed. However, I was also intrigued by Liang Shuming’s account of the western and Buddhist paths, and thus, became genuinely curious about the world in a philosophical sense.

After reading this book, all my life in the following 20 years seemed to lead naturally to the position where I am right now. Although I do not agree with everything that Liang Shuming said to me in the final winter of last century, his philosophy indeed sowed a seed of passion, a spark of inspiration to make me mindfully live my life and carefully plan my career. Right now, I am happily teaching philosophies and religions, both western and eastern ones, in an eldest liberal arts college of the U.S. Seen from this result, I am deeply grateful to that little small book which has tied my life to philosophy ever since.

So, dear friends, this is one central message I want to deliver in this first episode of introduction to philosophy: there are many paths to philosophy, and every human being has their own way to figure out how to live out their own life. However, regarding the thing called “philosophy,” according to my personal experience and learning, what it continually appeals to me is that it makes you think to answer all these most important questions for your life. These questions are:

What is the world surrounding me?

What is the purpose of my life? And,

What will I do for it?

Recommended Reading:

Thierry Meynard. “Liang Shuming’s Thought and Its Reception.” Contemporary Chinese Thought, Vol. 40, no. 3, Spring 2009, pp. 3-15.