Title: Duke of Zhou Made Rituals and Composed Music.

Hallo! This is Dr. Bin Song in the course of “Ru and Confucianism” at Washington College.

The first unit of our course starts from explaining a key concept of Ruist philosophy, 禮, normally translated as ritual or ritual-propriety, and its significance for us to understand the name of the tradition, 儒.

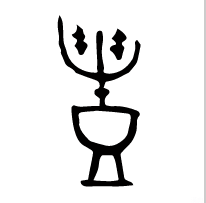

If we look into some earlier forms of the character 禮, it looks like a utensil holding jade or other rarities.

Quite visibly, the origin of the term 禮 pertains to religious ceremonies by which people follow customs and utilize facilities to express their pious feelings towards ancestors and other deities. Therefore, the normal translation of 禮, ritual or ritual-propriety, is quite literal. However, in the Ru school, the school that almost single-handedly took charge of inheriting, perfecting, and philosophizing ancient rituals in the context of ancient China, the meaning of 禮 greatly expands, and becomes a unique, hardly translatable, concept and perspective to ponder the overall nature of human civilization. Let’s read how the Classic of Rites describes this broad significance of 禮:

“The course of the Way, human excellence, benevolence, and righteousness cannot be fully carried out without the rules of ritual-propriety; nor are training and oral lessons for the rectification of manners complete; nor can the clearing up of quarrels and discriminating in disputes be accomplished; nor can the duties between ruler and minister, high and low, father and son, elder brother and younger, be determined; nor can students for office and other learners, in serving their teachers, have an attachment for them; nor can majesty and dignity be shown in assigning the different places at court, in the government of the armies, and in discharging the duties of office so as to secure the operation of the laws; nor can there be the proper sincerity and gravity in presenting the offerings to spiritual beings on occasions of supplication, thanksgiving, and the various sacrifices. Therefore an exemplary human is respectful and reverent, assiduous in their duties and not going beyond them, retiring and yielding – thus illustrating the principle of ritual-propriety.” (《禮記 曲禮》adapted from the translation of James Legge)

Here, any rule or convention that can lead to the re-ordering of an aspect of human civilization, such as individual moral self-cultivation, varying human interactions, education, the execution of law, the establishment of political institutions, leadership in army, court and other governmental offices, etc., can all be called 禮. In my frank opinion, there is really no singular English word which can capture this broad implication of 禮. Trying the best that I can, I would like to say 禮 is any “civilizational convention.” The philosophical reason why the Ru school came up with this concept to designate the essential nature of human beings is understandable: once having evolved with a capacity of using signs, symbols and languages to interact with the world, the relationship of humans to humans, and the one between humans and the nature are always mediated. In other words, humans interact with the realm of uncarved realities, the nature, through our interpretations of the meaning of these realities to us, and using a Ruist term, these human interpretations are constructed by our use of varying 禮. For instance, our mind reads people’s smiles in different ways, depending upon the cultural and societal environment we live in, and furthermore, we also interact with these smiles using postures and expressions fit for our purpose. Natural impulses such as those raw emotions of wonder, joy or anger, may play a certain role during this interaction, but they are all embedded in a much more complicated cognitive and emotional process mediated by our interpretations of the meanings of the world. Understood in this perspective, every means to mediate the relationships between humans and between humans and nature in a uniquely human way can all be called 禮. Therefore, my translation of it, civilizational convention.

In the Analects, the book that furnishes the most authentic record of Confucius’s deeds and sayings, there are plenty of scenarios where Confucius either talked of or actually performed ritual or ritual-propriety in the analyzed sense of civilizational conventions. He cared about any knowledge about the sacrificial rituals in temples, he talked of why people in his time needed to mourn for three years after their parents’ death, and other related topics, such as how to conduct human relationships, what are the best qualities of a state leader, what music is the most appropriate for a certain social occasion, and even how to stand, walk, speak, look, eat, etc. In fact, one of Confucius’s self-suggested missions is that because the system of ancient rituals in his time were collapsing, and music was decaying, so that he would try his best to learn, discover and even redesign the best rituals fit for his time, and then, he would teach and propagate these ideal rituals so as to recover social order and lay a solid foundation for the sustainable development of civilization. He called the entire body of these ancient rituals as “civilization” (文), and was quite confident to assert that the destiny of this civilization is on his shoulder. In extreme difficult situations, such as when he almost got murdered by political opponents during his exile, he relied upon this deep sense of mission and responsibility to strengthen his will of life, and eventually survive the distress.

However, a legitimate question for us to understand Confucius’s mission is that since he was a learner and advocate of ancient rituals, where were these ancient rituals come from? If he was the most respected teacher in the Ru tradition who has built the first private school to pass on ancient civilization to later generations, whom did he learn from? In the past several units of this course, we discussed Yao and Shun, these ancient sage-kings who had accomplished great deeds for Confucius to admire. But they lived thousands of years before Confucius, and Confucius’s admiration of them cannot be converted into the solid knowledge of their times. So, just like Americans who quite often evoke their founding fathers to make their contemporary moral and political cases, Confucius looked into the founding fathers of the dynasty he lived in, the Zhou dynasty, which had already endured about 500 years before Confucius. Among all these founding fathers of Zhou dynasty, one figure, the Duke of Zhou, whose name is Dan, stands prominently, and he turned out to be the most impactful figure on Confucius’s learning and teaching.

Let’s read several sayings in the Analects to understand this lineage of wisdom that Confucius tried to continue:

19.22 Gongsun Chao of Wei asked Zigong, saying, “From whom did Zhongni (Confucius) get his learning?”

Zi Gong replied, “The Way of Wen and Wu has not fallen to the ground. It is still there among the people. The worthy remember its major tenets, and the unworthy remember the minor ones, so the Way of Wen and Wu is nowhere not to be found. Where could not the Master learn from? Yet, what regular teacher did he have?”

7.5 The Master said, “Extreme is my decline! I have not dreamed of the Duke of Zhou for a long time!”

3.14 The Master said, “The Zhou sits on top of two previous dynasties. How rich and well developed is their civilization! I follow the Zhou.”

3.9 The Master said, “I could describe the rituals of the Xia dynasty, but the state of Qi cannot sufficiently attest to my words. I could describe the rituals of the Yin dynasty, but the state of Song cannot sufficiently attest to my words. This is because these states have inadequate records and worthies. If those were sufficient, I could adduce them in support of my words.”

2.23 The Master said: “the Yin (Shang) dynasty followed the rituals of the Xia, and wherein it took from or added to them may be known. The Zhou dynasty followed the rituals of the Yin, and wherein it took from or added to them may be known. Should there be a successor of the Zhou, even if it happens a hundred generations from now, its affairs may be known.” (Translation adapted from Ni, Peimin)

In the first two quotes, Confucius and his students indicated the origin of Confucius’s learning. It is the Way of Wen and Wu, and the teaching of the Duke of Zhou. These three mentioned figures, King Wen, who is the father of the other two, King Wu, the elder brother, and the Duke of Zhou are three most important founding fathers of the Zhou Dynasty. Among the three, Duke of Zhou’s role is the most significant since Confucius dreamed him all the time. And the last three quotes speak to the three major reasons why Confucius took the ritual system of Zhou as his primary masterpiece to learn and teach:

- First, The ritual system of Zhou Dynasty synthesized previous ones, and thus, represented the gist of ancient Chinese civilization in Confucius’s time.

- Second, Previous ritual systems are too remote to corroborate and study in details. But the Zhou rituals are well preserved in the state of Lu, which is the home state of Confucius, and also where the offspring of Duke of Zhou were enfeoffed.

- Third, the ritual system of Zhou Dynasty represents principles of human civilization that Confucius believes are eternal and everlasting so that any future generations, as long as they aspire to a sustainable civilization, still need to learn them.

Since Duke of Zhou was so important for Confucius’s learning, in the remaining part of this unit, we will focus on his personality, deeds, and his accomplishment in making rituals and composing music to eventually lead to Confucius’s admiration.

As indicated by the required readings, regarding the personality and the political accomplishments of Duke of Zhou, there were several major points to be honored by Confucius and later Ru scholars:

- 1, He helped his father, King Wen, and his brother, King Wu, to overthrow the last king in Shang Dynasty, and justified the conquest using a very new political theory: the legitimacy of rulership consists in the virtues of the rulers, which are confirmed by the support of the people. If a ruler succeeds to be virtuous and earn the support of their people, they will have the Mandate of Heaven, and thus, be legitimate to govern.

- 2, He helped his brother King Wu to govern the newly established state. In a crucial situation, he even would like to sacrifice his own life to secure his brother’s health. Also in light of his assistance to his father King Wen, Duke of Zhou represented the cherished family virtues such as filiality, and brotherly love in quite an eminent way.

- 3, When King Wu died, his son King Cheng was too young, and thus, Duke of Zhou had to act as a regent. On the one hand, he was the teacher of King Cheng so as to prepare his enthronement. On the other hand, when King Cheng was mature enough, Duke of Zhou fulfilled his promise and resigned from his regency. In this part of his story, Duke of Zhou was an uncle, a teacher, and a supreme governor, and he performed superbly in all of these three roles. Mostly importantly, his attitude towards political power earned much kudos from later Ru scholars: firstly, he was not obsessed with political power; when time is right, he would step down and yield to King Cheng as a subject. Secondly, his ultimate goal was to teach King Cheng to be a good ruler during the time of his regency, and this ideal of being an educator to political leaders quite fits the self-identity of later Ru scholars.

- 4, Duke of Zhou suppressed the rebellion in the eastern part of the country, punished its wicked leaders, appointed new leaders, and laid out a series of rules of government to stabilize the new dynasty.

In human history, I believe as long as any political figure succeeded to achieve similar deeds, they would be put on a pedestal to be memorized by later generations. However, the most important accomplishment of Duke of Zhou, from a Ruist perspective, still surpass the areas of self-cultivation, family-regulation, and governance. That took place in the form that Duke of Zhou established a whole system of rituals to reconstruct the entire Zhou civilization. This historical event was normally named by historians as “Duke of Zhou made rituals and composed music” (製禮作樂).

According to Wang Guowei (1877-1927), a prominent sinologist, there are three major breakthroughs that Duke of Zhou has made in this historic event:

- Firstly, he established the institution that kingship must be passed down to the eldest son in the royal family;

- Secondly, he re-organized the system of sacrificial rituals to one’s ancestors so that the relationship among different generations and branches of an extensive family is ordered;

- Thirdly, he prohibited marriage within a family of the same surname.

All these three major points of the Zhou ritual system are extremely important because Zhou dynasty is a feudal society, and the King appointed local political leaders according to their merits and their closeness of pedigree to the royal family. So, an elaborated family ethic to distinguish the duty and role of varying family members is crucial to the well-functioning of the entire political system. On the other hand, Duke of Zhou designed other aspects of the ritual system such as about how to recruit able people to fit government posts, how to distinguish offices, and how to hold many civil and religious ceremonies, etc.

Underlying all these concrete ritual arrangements of the newly established dynasty, there are several major principles that Confucius admired, and believed can guide human civilization for future generations:

Firstly, the purpose of ritual-performance is to cultivate people’s virtues so as to bring order to society. Although the blessing of deities and the divine power of Heaven were thought of as important, Duke of Zhou prioritized the role of humans in securing the blessing. In other words, in order to earn the divine support, humans need to primarily dedicate themselves to cultivating virtues through performing rituals. This spirit of humanism was continually developed in later Ruist thought.

Secondly, each human needs to fulfill their duty required by their role in a specific human relationship, and this role ethics, so-to-speak, was thought of as the foundation of individual well-being, social order and good government.

In a more concrete term, this second principle consists of the following aspects:

- First, 親親, that is to treat your family as your most close and important human fellows.

- Second, 長長, that is, within a family, the order of seniority is respected.

- Third, 男女有別, that is, men and women are different; marriage should not happen within the same family; and the right of a couple upon the management of their household must be fully respected.

- Fourth, 賢賢, that is, to respect people of good education and moral excellence. Accordingly, a key principle of good governance is meritocracy, which implies that a good leader must appoint the right people in the right positions.

On top of all of these ritual principles and initiatives, Duke of Zhou also composed poems, lyrics and music, and utilized these arts to educate the people of all these important ethical and political principles.

In a word, Duke of Zhou has cultivated great virtues, governed his country well, and more importantly, made rituals and composed music to lay a foundation for sustainable human civilization. Because of this, he was treated by Confucius as the most significant founding father of Zhou civilization, and became Confucius’s teacher secondary to none.

Required Readings:

“The Story of The Duke of Zhou,” compiled by Robert Eno in https://chinatxt.sitehost.iu.edu/Resources.html.

“The Announcement to Kang”, in the Classic of Documents, adapted translations by Bin Song from multiple sources.

Quiz:

1, In light of the etymology of the character 禮, what is the literal meaning of it?

A, religious ceremony/ritual

B, social etiquette

C, political institutuion

2, 禮 represents the distinctive nature of human civilization because:

A, the relationship between humans, and the one between humans and the nature are mediated by 禮.

B, uncultivated raw emotions have no role to play in human interaction.

3, Confucius described his own mission as to teach ancient rituals to all the people in order to recover social harmony for his time. Is this statement true or false?

4, Among King Wen, King Wu, King Cheng and Duke of Zhou, who is the eldest?

A, King Wen

B, King Wu

C, King Cheng

D, Duke of Zhou

5, which of the following reasons does not belong to the ones why Confucius chose the Zhou system of ritual as his target of learning?

A, the Zhou system of ritual is synthetic.

B, the Zhou system of ritual can be studied in greater details.

C, the Zhou system of ritual represents principles of human and civilizational thriving.

D, none of the above.

6, “Yet each time I bathe, I am called away three times, wringing out my hair in haste; each time I dine, I rush off three times, spitting out my food in haste, in order to wait upon some gentleman. I do so because I am always fearful that I may otherwise fail to gain the service of a worthy man.” This quote describes one governor’s willingness to respect and appoint talented people to the right governmental positions. Which governor does this depiction refer to?

A, King Wen

B, King Wu

C, Duke of Zhou

7, “O Feng, such great criminals are greatly abhorred, and how much more (detestable) are the unfilial (不孝) and unbrotherly (不友)! – as the son who does not reverently discharge his duty to his father, but greatly wounds his father’s heart, and the father who can no longer love his son, but hates him; as the younger brother who does not think of the manifest will of Tian, and refuses to respect his elder brother, and the elder brother who does not think of the suffering of his junior, and is very unfriendly to his younger brother.” Which principle of the Zhou ritual system do these words of Duke of Zhou’s represent?

A, reciprocal role ethics: every human needs to shoulder their duty defined by their role in a human relationship.

B, utilitarianism

C, deontology.

8, What have you learned from the thought and deed of Duke of Zhou? Please share your critical thought on this unit’s teaching.