Hallo, This is Dr. Bin Song at Washington College to muse about the History of Modern Philosophy.

After having discussed some of modern philosophies and their predecessors such as the pre-modern Aristotelian scholasticism, let’s ask an important question for the course: what is the beginning of modern philosophy after all? If you open textbooks on the history of modern philosophy, quite often, it is the French philosopher, Rene Descartes (1596-1650 C.E.), who is titled by historians as the father of modern philosophy. Notwithstanding not willing to contest this title, I would like to put the beginning of modern thought much earlier, not in Rene Descartes’s systematic philosophy which we will study in details later, but in Nicolaus Copernicus’s much technical work in astronomy. Today, we have another title to honor the work: we call it “The Copernican Revolution.”

Therefore, in order to understand the nature of modern thought, it is actually very significant for us to grasp the intrinsic connection between Descartes and Copernicus. To put it in a simple way, I would say Descartes’s “I think, therefore I am” can be seen as a philosophical magnifier of Copernicus’s much earlier, yet revolutionary astronomical theory. And let me explain why this is so in the following.

In order to more neatly and effectively explain the visual movements of heavenly objects observed from the earth, Copernicus put the sun, rather than the earth at the center of the universe, and he did so in reliance upon neither any of advanced technologies (since Galileo’s telescope had not yet been invented at the time of Copernicus) nor any of newly observed data of the sky. Instead, Copernicus believes his heliocentric astronomy is correct merely because 1) it can make pieces of a single astronomical theory more coherent to each other, and 2) such a new astronomical theory can explain the available data in a simpler way. What makes the story of the Copernican revolution even more compelling is that we know in a hindsight that given Kepler’s later revised heliocentric model which describes planets in the solar system move in ellipse rather than in circle, Copernicus’s theory is actually inaccurate. It has no higher degree of exactness or certitude regarding its description of heavenly movements compared with its predecessor, the dominant Ptolemaic geocentric astronomy, and this also means that Copernicus’s new theory would necessarily fail to produce a more accurate calendar and thus could not obtain those practical benefits which people widely expected the value of an astronomer’s job mainly consists in.

What makes Copernicus’s case even more imposing is that out of the concern of the controversial nature of his work, only towards the very end of his life, the year of 1543, Copernicus decided to publish it. This implies that despite having spending decades on the painstaking, tedious, and sometimes even seemingly hopeless work to calculate all those minute details of astronomical data, Copernicus could not even garner any personal benefit from the work: no fame, no money, and no expected change of Copernicus’s daily life before his death. If we can find any word from Copernicus’s own writings to answer our concern why he was motivated to pursue the work, we knew Copernicus’s major job was a Catholic canon, and he wrote to the Pope Paul III in the preface to his book on the Revolutions as follows:

“For a long time, then, I reflected on this confusion in the astronomical traditions concerning the derivation of the motions of the universe’s spheres. I began to be annoyed that the movements of the world machine, created for our sake by the best and most systematic Artisan of all, were not understood with greater certainty by the philosophers, who otherwise examined so precisely the most insignificant trifles of this world. For this reason I undertook the task of rereading the works of all the philosophers which I could obtain to learn whether anyone had ever proposed other motions of the universe’s spheres than those expounded by the teachers of astronomy in the schools.” (Translation and Commentary by Edward Rosen)

Therefore, it was out of a deep feeling of religious piety towards his almighty God, Whom he believes must have created the world out of sheer order, harmony and beauty, that Copernicus dedicated most of his life to working on a bravely new astronomical theory. But given all our previous analyses, just imagine how hopeless and dead-ended Copernicus’s work could have appeared to all the people surrounding him! It could neither bring any personal benefit to the astronomer in question, nor be accurate enough to produce any immediate practical benefits to the public. If piety can explain how Copernicus himself could sustain his efforts so long to eventually complete such an impossible work, why did such a work become revolutionary in its nature? In other words, why did the most brilliant minds in early Modern Europe, such as Galileo, Kepler, Descartes and Newton believe that Copernicus’s new thought, despite being inaccurate, is promising, and thus, would like to continue to work on it so as to finally create the whole paradigmatic change of human knowledge about the natural world?

In my view, this question is crucial for us to understand the connection between Copernicus and Descartes, and to answer this question, we still need to go back to the two criteria by which Copernicus judges his new heliocentrism is truer than the old geo-centrism.

Firstly, Copernicus thinks parts of his new system are more coherent to each other. For instance, in order to explain the diurnal westward and the annual eastward movements of heavenly objects, the old geocentric astronomy puts each star and planet on a gigantic universal sphere which rotates daily in a very fast pace surrounding the earth; however, for each of these stars and planets, it is within an orbit circling around the earth which moves annually in a much slower pace. The entire picture is like putting ants into different points of a gigantic wheel which all move in a direction contrary to the rotation of the wheel. How cumbersome and incoherent this entire system looks! However, in Copernicus’s heliocentric model, the sun is in the center, and all other planets move in an annual circle surrounding it with the earth also moving around itself in a daily basis. All the stars are put in an infinitely further distance from the solar system, and seen as a whole, the entire solar system just shares one single, common type of annual movement with each planet moving themselves locally. If God was thought of as an omni-intelligent creator, we could bet which model he would like to create the world according to!

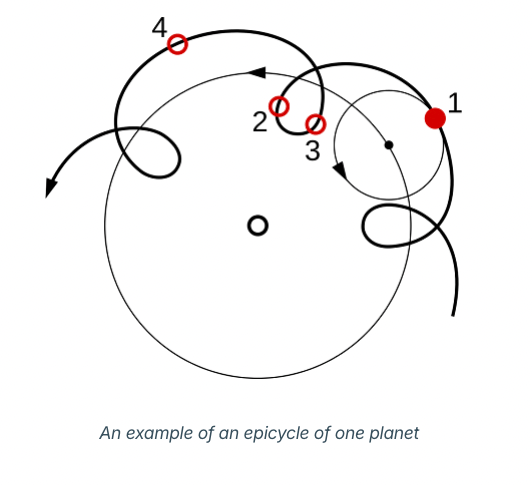

Secondly, Copernicus thinks the explanation made by his new system is simpler. For instance, the planets of the solar system wander in a strange way. During the overall annual eastward movement, they regress towards the west for a certain period of time and for several times during a year; this phenomenon is called “retrograde” of the solar planets. The solution by the old Ptolemaic model is to let planets move in an epicycle the center or one eccentric point of which moves on another circle called “deference,” and the center of the latter bigger, deference circle is the earth. In other words, seen from the perspective of the earth, Ptolemy’s geocentric model uses two circles to explain one phenomenon called the retrograde of planets. However, in Copernicus’s model, a planet moves on one singular big circle surrounding the sun in different velocities. Therefore, in some time of the year another planet will stay closer and closer to the earth, but in most of the time, two planets just constantly stay apart from each other. In other words, seen from the perspective of the earth, Copernicus’s heliocentric model uses only one circle to explain the same phenomenon, not even to need mentioning the complication of varying degrees of “eccentricity” of each epicycle in Ptolemy’s system. So, a simpler model is created by Copernicus to explain the same observed phenomenon.

However, let’s dwell in these two criteria for a while: coherence and simplicity. These two criteria of truth actually have nothing to do with perceived realities; rather, they are about the nature of human perceptions themselves. In other words, what drives Copernicus’s pursuit of an eventually inaccurate new astronomical model is not any practical result that his theory can bring to realities outside of human mind, which we know his theory can barely deliver according to our above analysis; rather, it is mainly about how human perceptions can get reorganized by themselves.

While refining Copernicus’s new perception of the solar world in a way more adequate to outside realities, modern scientists and philosophers had a long way to march. For instance, if the earth moves, how can we explain objects thrown upwards still fall upon the same place? If all planets move, what keeps them on their orbits? If the so-called sphere of stars is projected to be infinitely far away and therefore there is really no such a thing called the center of the universe, what is the position of human beings in this vast, seemingly entirely disoriented new world? As we will discuss later, all these triggered questions are continually answered by modern philosophers, and from the perspective of natural science, it is those scientists from Copernicus to Newton who have provided a somewhat complete system of modern science which utterly transformed human knowledge on the nature. From the perspective of social science and philosophy, it is philosophers from Descartes to Kant who have furnished a similarly somewhat complete system of enlightenment philosophy which functioned as an intellectual blueprint for all major aspects of modern society. However, at the very beginning of this chain reaction of modern thought lies the sheer desire of Copernicus to have human thought get organized by itself prior to demanding any practical consequence from it.

At this moment, I believe you are already being able to answer the connection between Copernicus and Descartes. Yes, “I think therefore I am” is actually a cartesian philosophical magnifier for the deeply transformative perspective brought by Copernicus’s astronomical work which manifests the nature of Modern Man as primarily the self-transforming power of individual human perceptions. Copernicus believes astronomy as “unquestionably the summit of the liberal arts and most worthy of a free man.” (Introduction, Book One, on the Revolution). As manifested by his work and life, such a transformation of human perceptions of the world, which is “revolutionary” by its very nature, requires the execution of human freedom, courage, disciplined and diligent use of human reason.

So, let’s let this conclusion of this lecture sink in our mind while we shall continually explore the history of modern philosophy: without any more empirical evidence to prove himself to be right, without any material benefits in vision to bring to either the public or himself, Copernicus spent his life inventing and perfecting a new theory which he believes to be true, and many of his followers also believe to be truer, just because the theory is more coherent and simple. Or should we conclude, Copernicus freely and rationally thinks, and therefore, the impact of his thought still exists during the centuries after his death.