(This article was firstly published at Huffington Post: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/a-catechism-of-ruism-conf_4_b_11607540.)

In several recent essays on dynamic harmony, the five cardinal human relationships and ten riciprocal duties, and the three guides and five constant virtues, I discussed many Ruist virtues. To help you understand the relationships among these virtues, I’ve created this Chart of Ruist Virtues. I encourage you to read the chart from the top down at first. (After you have a sense of the chart as a whole, however, you can contemplate it from any point.) Because I’ve already explained most of the terms on the chart in previous essays, I’ll focus here on the relationships between and among the terms.

The Chart in Detail

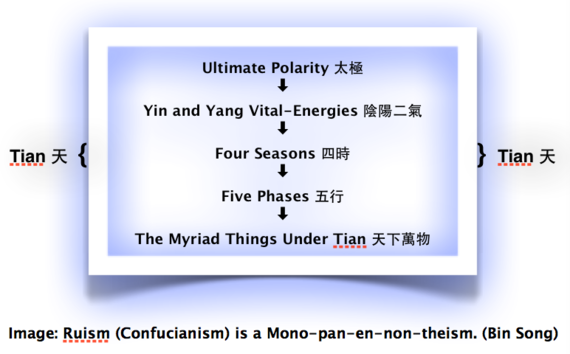

First, let’s discuss the Way of Heaven (Tian) (天道, Tiandao), which appears at the top of the chart. Tian refers to an all-encompassing, constantly creative cosmic power. Tian is the transcendent in Ruism. Literally, Dao means “the way,” but when these two terms are used together, Dao takes on a special meaning: it refers to the principle that runs through the all-encompassing power. By placing Dynamic Harmony (和, he) below The Way of Tian, we’re saying that Dynamic Harmony is the principle that runs through Tian. In other words, we can say that Dynamic Harmony is the Way of Tian. Because virtue (德) in Chinese can be extended to characterize the generic features of Tian, we can also say that Dynamic Harmony is a virtue of Tian.

The reason we can say that Dynamic Harmony is a virtue of Tian is because, as explained earlier, Tian’s creativity is all-encompassing. Everything that has ever existed, exists now, or will ever exist is brought into being by Tian and every being in the universe is part of Tian. In other words, as created by Tian, everything is and becomes together, which is the basic meaning of ‘dynamic harmony’. If we understand this, we can see that Dynamic Harmony is embedded in every aspect of this constantly-unfolding cosmic creation. We can also see that this all-encompassing force is neither anthropomorphic nor anthropocentric. In other words, Tian is not a person, nor is it exclusively focused on humans. As such, humans cannot directly access Tian per se, but must approach it through Ruist mysticism, a topic I’ll discuss in future writings.

The way humans engage with Tian concretely is to realize Dynamic Harmony in human society. We do this through the virtue of Humaneness (仁, ren). For this reason, you’ll see on the chart that the virtue of humaneness is the Way of Human Beings.

In Ruist ethics, Humaneness is the highest human virtue. In the most general sense, the virtue of Humaneness is the manifestation of Tian’s creativity within human nature. When we look in more detail, however, Humaneness includes five different facets, each of which refers to a different dimension of Humaneness:

Humaneness (仁, ren),

Righteousness (義, yi),

Ritual-Propriety (禮, li),

Wisdom (智, zhi),

Trustworthiness (信, xin)

We refer to these as the Five Constant Virtues (五常, wuchang). The Five Constant Virtues are universal principles that govern concrete human relationships. For this reason, the lower region of the chart describes how the Ruist tradition understands and describes particular human relationships.

First, let’s look at the Three Guides (三綱, sangang), a Ruist ethical understanding of three major human relationships. Originally, 君為臣綱 meant “ruler is the guide of subjects.” In a modern context, however, it ought to be understood as something like “in public life, a superior is the guide of subordinates.” This refers to relationships such as those between the state and citizens or between employer and employees. Likewise, although 父為子綱 originally meant “father is the guide of son,” a modern formulation would be something like, “parents are the guides of children.” Finally, 夫為妻綱, which originally meant “husband is the guide of wife,” should now be understood as “husbands and wives are the guides of each other, depending upon their different areas of expertise.”

The ethics of the Three Guides is a distillation of Mencius’ teachings about the Five Cardinal Human Relationships (五倫, wulun), which appear next in the chart. These relationships are parents and children, ruler and subjects, husband and wife, elder and junior, and friendship. Mencius taught that the virtues that guide each of these relationships are affective closeness (親, qin) between parents and children, righteousness (義, yi) between ruler and subjects, distinction (別, bie) between husband and wife, proper order (序, xu) between elders and juniors, and trustworthiness (信, xin) between friends.

The ethics of the Ten Reciprocal Duties (十義, shiyi) are described in an important chapter of The Book of Rites (禮記) called The Unfolding of Ritual Propriety (禮運). The text prescribes a single virtue for each person as they act out their role in these relationships. In the chart, for example, you will find that in the relationship between parents and children, parents should be guided by the virtue of parental kindness (慈, ci) and children should be guided by the virtue of filial devotion (孝, xiao). The practice of these two reciprocal duties by parents and children respectively will nurture the guiding virtue of affective closeness (親, qin) taught by Mencius in the Five Cardinal Human Relationships. This pattern of reciprocal virtues is repeated for the remaining four relationships.

The Big Picture

This chart of Ruist virtues suggests that each of us should cultivate the Five Constant Virtues — which can be seen as different facets of a single cardinal virtue, Humaneness (仁, ren) — so that we can play our roles well in a variety of human relationships. The ultimate goal is to create and sustain Dynamic Harmony in society, which is a concrete manifestation of the Dynamic Harmony of Tian’s all-encompassing creative power.

Notes on Interpretation of This Chart

When using this chart, there are two important caveats to keep in mind. First, you’ve probably noticed that some characters appear in this chart multiple times. This is because they represent different virtues depending on the context. At the top of the chart, for example, Humaneness (仁, ren) appears as the single cardinal virtue, the Way of Human Beings. In the section on the Five Constant Virtues below, however, it appears as one of the five virtues, and is taken in this context to refer to universal human love. Likewise, Righteousness (義, yi) appears in the Five Constant Virtues as the way human beings love appropriately in various situations. When Righteousness (義, yi) appears in the Five Cardinal Human Relationships, however, it is presented as the guiding virtue of the relationship between ruler and subjects and refers to the primary duty of both rulers and subjects to act appropriately toward each other.

The second caveat to keep in mind is that this chart is not intended to prescribe an ethical law that requires each Ruist to understand and practice these virtues one-by-one. This chart doesn’t contain every virtue cherished by Ruists over the past 2,500 years — after all, society is far too complex to be described by a single chart, and the ways in which each of us manifest these virtues in our daily lives will depend a great deal on the context in which we live.

So, although this chart is neither comprehensive nor prescriptive, it can serve as kind of reference chart to help you understand the backbone of Ruist ethical teachings. It is my hope that by studying, contemplating, and meditating on this chart, you will be better equipped to practice Ruist wisdom in your daily life.