[I deliver a speech “Prospects of Confucianism as Religion in light of Indonesia” to the Way of Wisdom (WOW) Confucian community in Indonesia on June 20/2020. Here is the audio record.]

Thanks a lot for inviting me to talk with Confucian friends in Indonesia. Liong, your passion inspires me, and thank you for organizing this wonderful forum! Mr. Budi Wijaya (姚平波), I know you may be here, your courage and persistence to fight for your right of marriage always remind me of what a genuine Confucian gentleman should do in a similar situation. So, thank you! And Mr. Kris Tan, I know you may also be here, thanks for teaching me of the life of a Confucian priest in Indonesia. I do hope there is a profession of Confucian priest in the U.S. as well, and that will be my No. 1 option for jobs outside the academy. And thanks also go to so many other people! Thank you for coming here. It is really a special honor for me to deliver this speech to such a special audience!

While learning the history of Confucianism in Indonesia, I get to know that Confucianism is one among six officially recognized religions, and normal people need to put your religious affiliation on your citizen ID card. If you do not have an identifiable religious affiliation, you will be disfavored by the society and the government in all sorts of visible or invisible manners that may bring unwanted consequences to your life. But Confucianism is not always so in Indonesia, I know that Indonesian Confucians fought very hard to obtain and maintain the status of official religion. The status is after all hard won, but not freely granted.

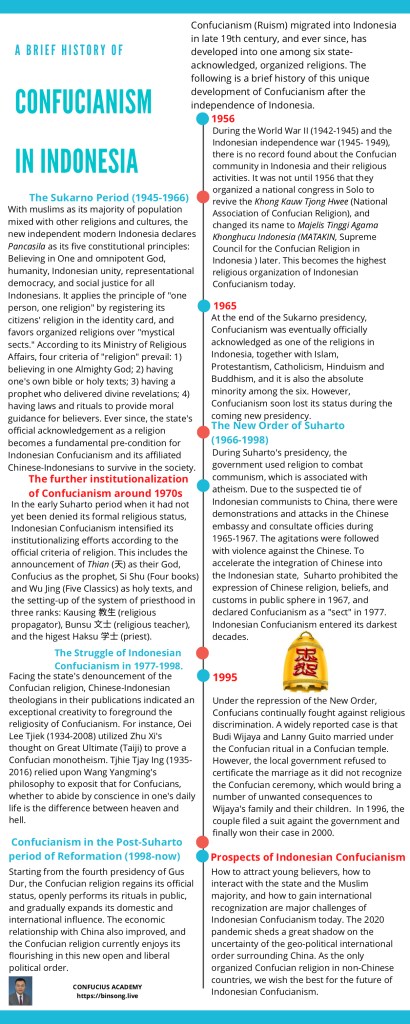

I will not get into too many details of the history about how Confucianism develops into an official religion in Indonesia in today’s talk. For friends who are interested in this topic, please go to my website, and I make a series of posters to explain this. I also share my screen of the posters here, you can get an initial look.

From the history of the Confucian religion in Indonesia, I get to know and admire how special Indonesian Confucianism is in comparison with other forms of Confucianism developed in other countries and in different periods of history. I will highlight three major features of Indonesian Confucianism in this speech.

First, the emigration of Confucianism to Indonesia happened in a very special time. That is in late 19th century, when most of East Asian Confucianisms were either declining or facing unprecedented challenges from the Western colonial powers such as in China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam. During that time, the Dutch colonial government in Indonesia took a racially stratified system, and labeled Chinese immigrants as the second tier of citizens called “Foreign Orientals”, which is lower than European White people, but slightly higher than indigenous Indonesians. In this system, race, religion, culture, and economic and politic statuses are all lined up together in order for the Dutch government to bring order to their colony. Obviously, in this situation, if all your fellow citizens have a religion, you have to develop one on a par as well. Otherwise, without a religion, you will be either converted to other racial groups and accordingly undermine the solidarity of your own community, or have to bear all undesirable consequences as a religionless person. And this term, “being religionless,” in the environment of colonial Indonesia and afterwards, is always a derogatory one. In a word, the initial impetus of Indonesian Confucianism as a religious movement pertains to an issue of survival, an issue of living, living better or worse, rich or poor, an issue whether your kids can go to good schools, and whether you can continually and safely bring food to the table to feed your family. It is a historical must-do, and it does not entirely derive from free deliberation or voluntary association of a group of believers to form a religious organization. That is the first point I need to highlight for understanding the very special Confucian religion in Indonesia.

Second, the political pressure from the Indonesian government to force Chinese Indonesians to choose and organize their own religion is even higher after Indonesia’s independence in 1950s. Since the Sukarno presidency of the independent Indonesia, the so-called old order regime, the Indonesian government adopts four criteria of religion, which are highly influenced by the country’s Muslim majority’s understanding of religion: 1) if some tradition is counted as religion, it must believe in “Almighty God,” 2) it must have its own bible or holy text, 3) having a prophet who delivered divine revelation, and 4) having laws and rituals to provide moral guidance for believers. Meanwhile, the Indonesian government also took the policy of “one person, one religion” by registering its citizens’ religions in their identity card. The darkest age of Indonesian Confucianism came under the New Order of Suharto presidency. The government at that time was highly suspicious towards the tie of Chinese Indonesians to Chinese communism, and repealed the official status of religion of Confucianism. At this time, indigenous people who happened to be hostile to Chinese Indonesians also found a way to release their resentment in violence. This situation lasted for about 30 years, and Indonesian Confucians underwent a massive number of conversions to other religions, most likely Christianity or Islam, because of the unsustainable lifestyle due to their Confucian identity. Even so, there were sparks of hope, persistence and strength in this pervasively difficult days and years for Indonesian Confucians. A widely reported case is that Mr. Budi Wijaya, one of my best Indonesian Confucian friends, and his wife Ms. Lanny Guito married through the Confucian ritual in a Confucian temple. However, the local government refused to certificate the marriage as it did not recognize the Confucian ceremony as legal. This would surely bring a number of harmful impacts upon Mr. Wijaya’s family and children. In 1996, the couple filed a suit against the government, and only after the Suharto presidency ended, the couple finally won their case in the year of 2000. In a word, the issue whether to sustain Confucianism as a religion after Indonesia’s independence for Indonesian Confucian believers is still primarily an issue of survival. It is about whether you can get married legally, whether your children would not be bullied in their schools, and whether you can continually live out a safe and decent human life in an overall unfriendly environment relying upon your deep spiritual power rooted in your faith. In this way, for discussing whether Confucianism is a religion, Indonesian Confucianism distinguishes itself from other forms of Confucianism in that it has a very solid political ground, and a very fixed conceptual framework to frame the debate. Even if scholars may disagree with answers given by Indonesian Confucian thinkers to the debated question, I am extremely sympathetic with the utterly real social situation that Indonesian Confucianism constantly faces, and I also genuinely admire its creativity, persistence, and hopefulness as a result.

Third, because of the special features of Indonesian Confucianism in its time of inauguration, its largely immigrative status, and its inevitable domestic and international geo-political involvement, it is also special in its third feature that I truly admire and appreciate. That is the creativity of thought and practice in its daily Confucian way of life. I will elaborate this using two major points:

Firstly, the textual and vocabulary base of Indonesian Confucianism is fairly unique. At the point of time when Chinese Indonesians were driven to organize their own religion, most of them could not speak or read Chinese. Therefore, they mainly relied upon European or Malay translations of Confucian classics. As we know, every translation is an interpretation. Together with the pressure of religionizing Confucianism due to the policy of the Dutch colonial government, these sources provided a fairly unique angle to look at traditional Confucian classics. For instance, Indonesian Confucianism highlights the religious terms and concepts in classical Confucian texts, such as 上帝 (upper-lord), 天命(divine command), that were once highlighted by the translations of early Christian missionaries. However, the purpose of these Christian missionaries to laser focus upon these terms in Confucian classics is to prove there are seeds of religious truth in classical Confucianism so that the spread of Christianity can fulfill them, can make them grow. In other words, the selection of Confucian terms for such a translation is actually the strategy of Christian missionaries to convert Chinese literati. However, the conversion to western religions is always the No.1 concern of Confucian believers in Indonesia, so, different from those Christian missionaries, Indonesian Confucianism also utilized European enlightenment thinkers’ writings on Confucianism to argue for the modern and advanced nature of Confucian thought. In combining these two apparently contradictory European interpretations of Confucianism, Indonesian Confucianism accomplished a mission impossible to fit its unique communal, racial and political needs. Let’s use an example to illustrate how special this is. My friend Kris Tan informs me that using English terms, the Indonesian translation of the first chapter of Zhong Yong, one of the Confucian four books, can be understood as such: “The Word of Tian is called the True Nature. Doing to follow the True Character is named after taking the Holy way. And Guidance to take the Holy way is called Religion.” Here, “word” “holy way” and “religion” all remind us of the need of religionizing Confucianism according to the Abrahamic definition of religion. However, the emphasis on “true nature” of humanity, or “true character” of human individuals also makes the intrinsic tension in Abrahamic religions between divine and human natures almost entirely disappear. When reading this translation, I cannot help asking myself: can it still be counted as a Confucian tenet? I think it is absolutely yes, but the translation looks familiar while being novel and fresh. I am also highly confident to say that it serves very well the needs of Indonesian Confucians. For me, all of these are signs of the genuine creativity of Indonesian Confucianism as a religious movement.

Secondly, not only in translation, the creativity of Indonesian Confucianism also consists in how it selects traditional sources throughout the entire history of Confucianism to make its case and serve its own distinctive needs. Per the four aforementioned criteria of religion established by the Indonesian government, we find there is actually no uniform expression of such a religion in the history of Confucianism. The tradition before Confucius was more religious, but it is less religious during the time between Confucius and Xunzi when humanism and practical rationality were rising; under the influence of Yin-Yang theory and folk religious practice, Confucianism in Han Dynasty became more religious again, but in Song-Ming Neo-Confucianism, the tradition went back to the less religious route as it claimed to continue the lineage of Dao initiated by Confucius and Mencius. In particular, the aforementioned criteria of religion require that Confucius is a prophet and delivers divine revelation. Throughout the entire history of Confucianism, we find only the New Text school of Confucianism in Han Dynasty furnishes a similar narrative to say that Confucius was born because of his mother’s divine encounter, and Confucius was therefore worshiped as an uncrowned king to prescribe laws and orders for later generations. This deified image of Confucius, the magical worldview, and the accordingly very progressive political philosophy in the New Text Learning of Confucianism were largely ignored after Han Dynasty, and only until Qing Dynasty, more than one millennium later, it revived again to become a major source for Confucian scholars’ reformative political thought. In 1903, Kang Youwei, a major voice of the New Text learning in late Qing Dynasty, visited Indonesia, and passed on his idea of the Confucian religion to Indonesian Confucians. Ever since, this New Text Learning becomes a foundational source for Indonesian Confucians to argue for their case and organize their institutions. However, as indicated in the case of translation, there are other forms of Confucian thought, or other forms of Confucian religiosity in the tradition. If we change the definition of religion, we will find the spiritual way of life that is constructed by the so-called Neo-Confucianism in mainly Song-Ming dynasty of China and other East Asian countries is actually the most prevalent and influential form of Confucian religion regarding the space it has reached and the time it has gone through. In this Confucian religion, Confucius is not a deified prophet any more, but a sage to inspire humans to live a fulfilled human life here and now. So, what does Indonesian Confucianism do with this dimension of Confucian religiosity? Again, while maintaining the basic framework of New Text learning as its major source to argue for Confucian religion per the criteria of Abrahamic religions, Indonesian Confucians incorporated Neo-Confucianism as much as they can to serve their distinctive needs. For instance, some Indonesian friends informed me that Mr. Tjhie Tjay Ing (1935-2016, forgive my pronunciation if it is wrong) was the best Confucian theologian in Indonesia in his generation. While debating with people dubious of the claim that Confucianism believes in afterlife in the highly oppressive period of Suharto presidency, Mr. Tjhie Tjay Ing, on the one hand, cites texts in the Classic of Rites to indicate that two sorts of souls were thought of as surviving the death of human body, and on the other hand, Mr. Ing also uses Wang Yangming’s thought in Neo-Confucianism to emphasize that for Confucianism, whether to abide by one’s conscience at each moment of human life determines whether one lives in a hell or a paradise here and now. See how creative this is! How convincing this is! As indicated by the example, we can say Indonesian Confucianism adapts to the need of folk religious practice in ancestor worship, but still keeps the very this-worldly, and deeply spiritual Confucian attitude towards human life here and now.

Good, at this moment, my speech covers three very special, and major features of Indonesian Confucianism: its initiative in the period of Dutch colonial government, its sustaining effort after Indonesia’s independence, and its creativity. The biggest lesson I learned from this very unique, on-going process of Confucian religion in Indonesia is that religion does not yield. Yes, let me repeat this, religion does not yield. Human activities are always constrained by varying objective forces such as politics, economy, geography, family history, etc.; however, the deep spiritual power of humanity rooted in their faith as it is articulated by a specific tradition never yields. It just makes use of whatever is available to create whatever is useful to make people’s life better and worth living. I am informed that when Indonesian Confucians travelled to the mainland of China nowadays, they found some mainland Confucian scholars dismissed the idea and the practice of Confucianism as a religion; this is highly understandable given the overall atheistic state ideology in the mainland of China now. However, if we learn the history of Indonesian Confucianism and actually talk with Indonesian Confucian friends, we will understand how perfect the sense is to make Confucianism a religion in their situation. They just have to do so. As I mentioned time and time again, for Indonesian Confucians, whether Confucianism is a religion is not primarily an issue of academic debate. It is an issue of survival, an issue of whether human life matters, and an issue as tangible and concrete as whether you can marry to someone you love. There is a Chinese idiom to say that only when forced into a corner of death, one can re-gain their life. (置之死地而後生) Yes, this is exactly what I found in the case of Indonesian Confucianism. Confucianism almost died out in late Qing Dynasty, but in Indonesia, it is the indomitable will of life of the people that make it alive again. So, as a Confucian scholar, I would say, thank you, Indonesian Friends, you, your family and your ancestors have done something extraordinary that is truly admirable.

Before ending my speech, I want to talk of briefly Confucianism in the U.S. and the contemporary world at large, since the title of this speech implies my prospects of Confucianism in the future.

When I learned the history of Indonesian Confucianism, I keep rethinking of my own experience of growing up to become a Confucian scholar and practitioner. Although there is no time for me to share with you my personal experience of Confucian practice in this speech, I hope there is further opportunity for me to do so in the future. However, one of my central foci in my work in the U.S. is indeed trying to increase the public awareness of the Confucian tradition in the English-speaking world. In the recent decades, I studied with the so-called school of Boston Confucianism, I organized the first college student Confucian group in the U.S., titled as Boston University Confucian Association. Right now, I am also helping to organize an educational organization called Ruist Association of America (RAA), and teach, research and speak on Confucianism in the academy.

As I commented above, religion does not yield. The will of life does not yield. This means no objective situation can eventually smother a tradition as long as its faith is kept and prevails. But it also means the way of religionzing one tradition in one situation may not be fit in another one. If we look into the situation of Confucianism in the U.S., we find those powerful factors that drive Confucianism into being organized as a religion in Indonesia do not apply. The emigration of Chinese or East Asian Americans into U.S. happened even later than the one into Indonesia, and it happened after when Confucianism was radically critiqued by Chinese intellectuals themselves in the early 20th century. This means there is no natural attachment to the so-called Confucian tradition in most of Chinese Americans. Also, there is no strict lining-up of race, culture and religion in America as it happens in Indonesia, and therefore, the life of faith for Chinese immigrates is actually very diverse and in a certain sense, de-centered. In particular, according to social surveys conducted in recent years, the traditional organized way of religious life in the U.S in general is declining. There is a growing percentage of people identifying themselves as religious “nones” or “being spiritual but not religious.” My friend, Ben Butina, and I, did a similar survey to clarify the perception of ordinary American people about Confucianism. We find that the majority of ordinary Americans do not see Confucianism as a religion, but as a philosophy or a way of life. All of these guide my own thinking, practice, and teaching on Confucianism in the U.S, which may be different from the one that is organized under the very strict criteria of “religion” explained above.

However, no matter what a concrete pattern of Confucian life that America could take in the future, one thing remains sure for me from my knowledge of Indonesian Confucianism: the Confucianism that could be counted as a possible, significant portion of American spiritual life must be down-to-earthly real. It must be as real as what Indonesian Confucianism has gone through. In other words, it needs to poke people’s nerves, go under their muscles, and sink in the depth of people’s heart, in whatever ways this can be imagined or expected.

The following is a preliminary list of potentials that Confucianism has, and which I also hope can help Confucianism to achieve this down-to-earthly real presence in the U.S. and in the contemporary world at large. This is not an easy list to do, but I do believe it is hopeful.

First, the Confucian wisdom on harmonization in the realm of government, social and business management can help to transform the highly polarized politics in the U.S. and other countries that are having a similar problem.

Second, the human-centered pedagogy of liberal arts in Confucianism can inspire unity for the highly compartmentalized institution of education, and thus, bring more integrity to students and scholars’ life.

Third, the spiritual practice of Confucianism to focus on meditation, arts, and minor ritual details of human daily life is that type of spiritual life which modern professionals are longing for.

Fourth, the Confucian wisdom on a balanced community life between authority and individual autonomy can enlighten how faith communities get organized in the contemporary world.

Of course, this list can go on, and people may have different prospects of Confucianism per their own judgment. But a bottom line is that, let me repeat it, human life is primarily about survival, subsisting, and participating the eternal meaning of life here and now. Whether Confucianism can prevail here and there in the world will be decisively dependent upon whether it can operate itself well along this bottom line, as it is so vividly indicated by the case of Indonesian Confucianism. In particular, since Indonesian Confucianism has its own very robust organized forms right now, I also hope the aforementioned four prospects of Confucianism can be vividly and continually manifested in Indonesia as well.

Good, this will be the end of my speech. Thanks for the invitation again! And I look forward to more conversations with you during the Q and A section.